At a City Hall hearing this morning, I witnessed the breadth and depth of the forces that have aligned behind financing a new airport terminal with private funds — an approach I think is risky and far too costly.

The public hearing was before a joint session of two City Council committees, the Airport Committee and the Finance and Governance Committee. The issue at hand was an ordinance, sponsored by Councilwoman Katheryn Shields, that calls for the city to be in charge of constructing a new airport instead of relinquishing control to Burns & McDonnell or another private company.

Specifically, Shields’ ordinance provides for the city Aviation Department to issue up to $990 million in revenue bonds, which would be paid off with an estimated $85 million a year in revenue generated by airport operations, including airline gate rentals and per-passenger fees the airlines have to pay the city. Also going toward the $85 million a year would be the city’s share of concessions and parking revenue.

About 10 people — many of them representing groups with vested interests — testified at the hearing. And all but one — me — spoke against the public-financing option. (The committee took no action on the ordinance; it will be considered again at a future meeting.)

A few people specifically expressed support for the widely publicized Burns and Mac proposal, including Patrick “Duke” Dujakovich, president of the Greater Kansas City AFL-CIO, who called Burns and Mac “the hometown team.” Dujakovich is a key figure in the debate because his organization represents most of the building and construction trades unions whose workers who would build the terminal.

Others who spoke in favor of private financing included representatives of organizations that advocate for women- and minority-owned construction firms.

A common assertion of the private-financing advocates was that Kansas City voters would be more likely to approve a project that is done with private funds as opposed to city-issued revenue bonds.

That may be true — at least right now, before an election date has been set and a campaign has been launched — but there are some significant down sides to private financing.

For one thing, I basically don’t like the idea of ceding control of the biggest project in city history to a private company — any private company. The overarching goal of any private company is, first and foremost, to make a profit. The city’s mission, on the other hand — and that of any public entity, by extension — is to provide good facilities and services for the public. Nobody at City Hall is going to get a $100,000 bonus if the project turns out well.

But the main advantage to the city retaining control and issuing revenue bonds is it could obtain financing at an interest rate 1 1/2 to 2 percent lower than what a private company would have to pay to borrow the money from conventional sources, such as insurance companies.

In remarks at today’s hearing, Shields estimated that over the life of a 30-to-35-year bond issue, the interest savings could be as much as $400 million. A local bond expert who was at the meeting told me privately he thought the difference would be closer to $200 million.

As I told the committee members, though, whether it’s $200 million, $300 million or $400 million, that is a ton of money, enough to constitute “an overpowering argument” in favor of public financing.

Shields emphasized that all the money needed to pay off city-issued revenue bonds would come from the airlines, plus concession and parking operations. General city revenue would not be tapped and would not be at risk. (As an aside, the Aviation and Water departments are the city’s only two “enterprise departments,” so named because they operate completely on the revenue they generate from their operations and fees rather than on general city tax revenue.)

Burns and Mac has attempted to counter the financing disparity by asserting it could build the new terminal in four years instead of the six that the city has estimated. But as I told the committee today, you never know what’s going to happen in a major construction project, and predictions on how long it will take to finish a major project are educated guesses, at best.

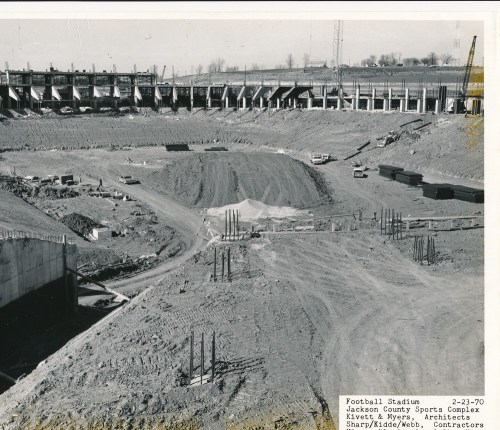

For example, early in my career as a KC Star reporter, I covered construction of the Truman Sports Complex. Along the way, a construction trades strike developed, and work came to a halt. The general contractor was helpless. And Jackson County, which had issued voter-approved general-obligation bonds to build the stadiums, could do little. It was so bad county officials fired the executive director of the Sports Complex Authority and replaced him with someone they thought could help resolve the impasse. Work eventually resumed, but precious weeks were lost.

(Coincidentally, yesterday was the 50th anniversary of the vote to approve the sports-complex bonds.)

**

Another issue that came up today, as I alluded to earlier, was the perceived lack of voter confidence in the city’s ability to pay off nearly $1 billion in revenue bonds.

To that I say balderdash.

On April 4, Kansas City voters dramatically and resoundingly demonstrated their confidence in the city when they overwhelmingly approved an $800 million general obligation bond issue to address a variety of needs, including new sidewalks, road and bridge maintenance, flood control, a new animal shelter and upgrades to city buildings to comply with the federal Americans with Disabilities Act.

Here’s how I closed my remarks today:

“If the need is clearly demonstrated, the financing well explained, and if residents are presented with an appealing design, I think we will have a successful airport election and we’ll all be winners — even those who are loath to part with their beloved horseshoe terminals at KCI.”

I fully believe that. I also believe it’s crazy to fork over $200 million or more in unnecessary interest payments. Eventually, that money could be spent on airport operations, amenities and additional improvements, instead of pissing it away on interest.

You must be logged in to post a comment.